Gloria Kim, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University of Florida’s Department of Engineering Education, found her research area organically. Her life experiences were directly related to convergence in education, not that she knew it at the time.

She grew up in Australia, Canada, Germany and Korea, learning three languages, moving to the United States, earning her bachelor’s in chemistry, and earning her master’s and doctorate degree in biomedical engineering. These were the experiences that all converged at the University of Florida when she joined the faculty of the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering in 2010 and again in 2019.

Kim’s focus on engineering education research and practice began with her first National Science Foundation (NSF) grant in 2014. It has continued internationally through partnerships with South Korean universities and research institutes.

“The cultural shock I experienced when transitioning from chemist to biomedical engineer was a wake-up call. I was prepared for the intellectual challenges of entering a new field, but not the accompanying shift in my mindset and identity as a researcher,” she said.

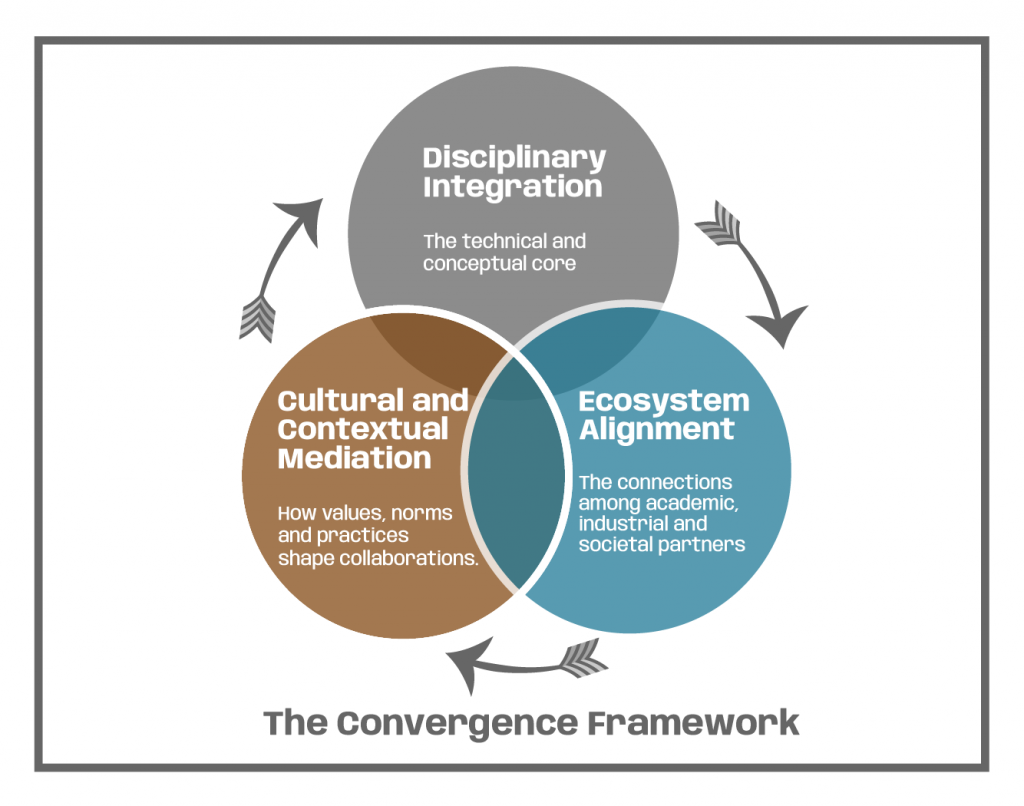

“That experience shaped my view of convergence in engineering education. Interdisciplinary models connect existing fields; convergence invites students to co-create new frameworks and shared identities across disciplinary and cultural boundaries.”

Convergence is the action of unrelated things moving toward each other to join or meet at a common point. Ideas can converge, for example. Convergence in education is a transdisciplinary approach to teaching that integrates knowledge, skills and technologies from different fields to solve complex, real-world problems.

Question: Why do you think focusing on convergence in engineering education is important?

Kim: My educational background revealed that beyond mastering disciplinary fundamentals and technical skills, the ability to understand and integrate knowledge across fields has become essential for addressing increasingly complex engineering problems.

How does your concept of convergence in engineering education differ from traditional models of interdisciplinary or integrated curricula?

The study-abroad and research-abroad programs I have developed at UF immerse students in global, cross-disciplinary projects where they learn to negotiate meaning, values and methods with peers and international partners. This approach has produced strong outcomes.

Students report greater adaptability, intercultural awareness and confidence in ambiguous, real-world settings. At the same time, some initially struggle with the uncertainty of not having a clear disciplinary “home,” but that discomfort often becomes a catalyst for their professional growth and collaborative maturity.

How has the partnership with South Korean universities and research institutions informed the convergence framework you’re developing?

First, I learned the value of building learning experiences where students jointly define problems, methods and outcomes. Second, I came to view culture as a design variable rather than a background condition; the way students approach hierarchy, teamwork and empathy changes how convergence unfolds. Finally, these collaborations highlighted the importance of ecosystem-level convergence, linking academia with research institutes and industry partners in workforce development.

What skills do you see emerging in UF students who participate in these international visits?

Through their international experiences, UF students develop adaptability, intercultural fluency and collaborative resilience as they learn to navigate unfamiliar communities, communication styles and problem-solving approaches. These mindsets translate directly into their future careers by enabling them to lead diverse teams, design context-aware technologies and innovate effectively across organizational and cultural boundaries.

What challenges have surfaced when aligning UF and Korean institutional goals?

In Korea, teaching assistants often play a more administrative or hierarchical role, while at UF they are expected to take on facilitative, student-centered teaching responsibilities. Navigating these differences has become a learning opportunity for students who experience firsthand how academic culture shapes communication, leadership and collaboration.

How do you assess the impact of overseas collaborations on the broader engineering education community?

Academically, the programs have led to new course modules at UF and seven Korean universities, joint publications and student research pathways that embed global and interdisciplinary perspectives into UF’s engineering curriculum.

Culturally, the collaborations have sparked greater interest and participation among engineering faculty, helping to cultivate an expanding community of globally minded educators across UF.

What advice would you give educators in other institutions who wish to adopt a convergence model and build meaningful international collaborations?

Students and international partners vary in their comfort levels when engaging across disciplines and cultures, so it is important to spend time getting to know them and begin with small, intentional steps. I review the class roster and their icebreaker write-ups, which helps me identify ways to connect the material to their disciplinary foundations and cultural contexts.

I would emphasize starting small, co-designing with local partners and treating collaboration as an evolving relationship rather than a fixed project.